𝘚𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘪𝘦𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘭𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘢𝘯 𝘶𝘯𝘦𝘹𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘫𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘯𝘦𝘺 𝘪𝘯 𝘧𝘪𝘯𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘦.

There is an old punchline that has circulated through businesses for decades. It usually comes up when a salesperson is defending a discount, or a founder is justifying a cash-burning growth strategy:

“Sure, we lose a little money on every unit we sell… but don’t worry, we’ll make it up in volume.”

It always gets a laugh because the math is so obviously broken. If you lose a dollar on one sale, selling a million of them just means you lose a million dollars.

For many companies, this is the silent killer. They aren’t failing because they lack vision. They are failing because their core “atomic unit” of business is broken.

The Lemonade Stand Reality Check

In a previous post, we talked about Gross Margin using the 𝗖𝘂𝗽𝗰𝗮𝗸𝗲 𝗦𝗵𝗼𝗽 𝗧𝗲𝘀𝘁. We determined that if the ingredients cost $3 and you sell the cupcake for $5, you have a $2 gross margin. That tells us the product itself is profitable.

But Unit Economics asks the uncomfortable question that comes before you sell the cupcake:

How much did it cost to get that customer to walk into the shop?

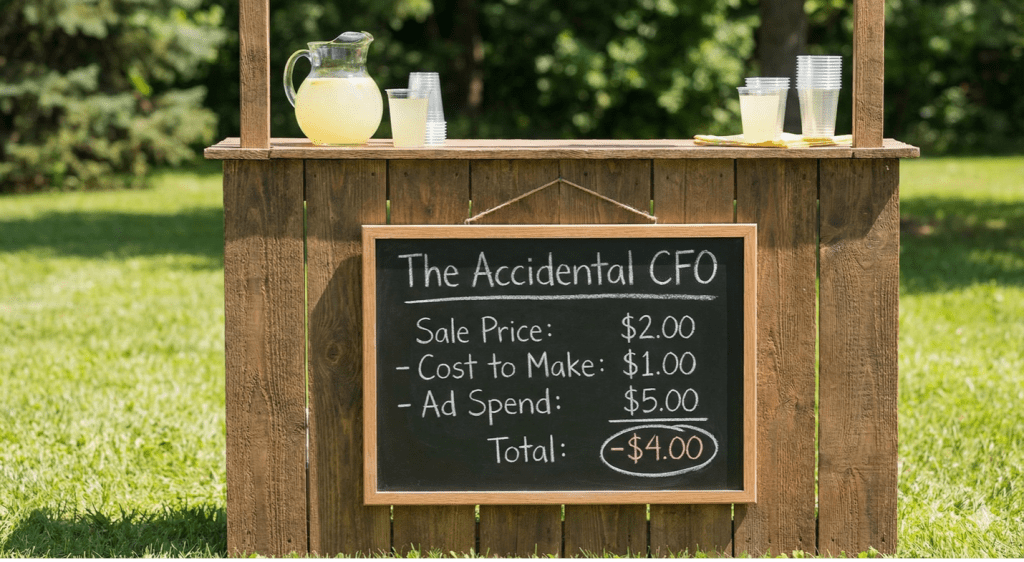

Let’s say you are running a lemonade stand.

🍋 Cost to make: $1.00

🍋 Price: $2.00

🍋 Gross Profit: $1.00 (Looks good!)

But… what if you had to spend $5.00 on ads to find the one person who bought that cup?

Suddenly, you aren’t making $1.00. You are losing $4.00 every time you “succeed” at finding a customer.

This is the difference between Gross Margin (product health) and Unit Economics (business model health). If you try to “make it up in volume” here, you aren’t growing a business; you are aggressively funding a disaster.

The Truth Serum: CAC and LTV

To fix this, you have to look at two acronyms that serve as the CFO’s truth serum:

- CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost): The total cost to get a customer through the door (Marketing + Sales).

- LTV (Lifetime Value): The total profit you make from that customer before they leave you forever.

The Golden Rule? You generally want an LTV:CAC ratio of 3:1. For every $1 you spend finding a customer, you should make $3 back over time. If you are sitting at 1:1, you are running on a treadmill just to stay in the same place.

💡 The Accidental CFO Takeaway

Founders often hate this math. It bursts the valuation bubble. It forces you to admit that maybe the product is too cheap, or the marketing is too expensive.

But as I wrote previously, 𝗜𝗻𝘁𝗲𝗴𝗿𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝗜𝘀𝗻’𝘁 𝗢𝗽𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝗮𝗹. Admitting your unit economics are broken is the first step of honest leadership.

If the math doesn’t work for one customer, it won’t work for one million. You cannot outrun bad unit economics.

Question for the comments: Have you ever worked at a company that tried to “make it up in volume”?

#TheAccidentalCFO #UnitEconomics #inersec #CAC #LTV

Leave a comment